In this section, we present and compare the results of the eleven

approaches on the four document data-sets. Clustering quality is

understood in terms of mutual information and balance.

For each data-set we set the number of clusters ![]() to be twice the

number of categories

to be twice the

number of categories ![]() , except for the REUT data-set where we

used

, except for the REUT data-set where we

used ![]() since there are many small categories.

Using a greater number of clusters than classes

allows multi-modal distributions for each class. For example, in

an XOR like problem, there are two classes, but four

clusters.

since there are many small categories.

Using a greater number of clusters than classes

allows multi-modal distributions for each class. For example, in

an XOR like problem, there are two classes, but four

clusters.

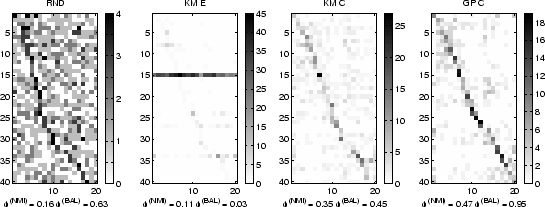

Let us first look at a representative result to illustrate the

behavior of some algorithms and our evaluation methodology.

In figure 4.3, confusion matrices illustrating quality

differences of RND, KM E, KM C, and GP C approaches on a sample of 800

documents from N20 are shown.

The horizontal and vertical axis correspond to the categories and

clusters, respectively. Clusters are sorted in increasing order of

dominant category. Entries indicate the number

![]() of

documents in cluster

of

documents in cluster ![]() and category

and category ![]() by darkness. Expectedly,

random partitioning RND results in indiscriminating clusters with a

mutual information score

by darkness. Expectedly,

random partitioning RND results in indiscriminating clusters with a

mutual information score

![]() . The purity

score

. The purity

score

![]() indicates that on average the

dominant category contributes 16% of the objects in a

cluster. However, since labels are drawn from a uniform distribution,

cluster sizes are somewhat balanced with

indicates that on average the

dominant category contributes 16% of the objects in a

cluster. However, since labels are drawn from a uniform distribution,

cluster sizes are somewhat balanced with

![]() . KM E delivers one large cluster (cluster 15) and many small

clusters with

. KM E delivers one large cluster (cluster 15) and many small

clusters with

![]() . This strongly

imbalanced clustering is characteristic for KM E on high-dimensional

sparse data and is problematic because it usually defeats certain

application specific purposes such as browsing. It also results in

sub-random quality

. This strongly

imbalanced clustering is characteristic for KM E on high-dimensional

sparse data and is problematic because it usually defeats certain

application specific purposes such as browsing. It also results in

sub-random quality

![]() (

(

![]() ). KM C results are good. A

`diagonal' can be clearly seen in the confusion matrix. This

indicates that the clusters align with the ground truth categorization

which is reflected by an overall mutual information

). KM C results are good. A

`diagonal' can be clearly seen in the confusion matrix. This

indicates that the clusters align with the ground truth categorization

which is reflected by an overall mutual information

![]() (

(

![]() ). Balancing is good as well with

). Balancing is good as well with

![]() . GP C exceeds KM C in both aspects with

. GP C exceeds KM C in both aspects with

![]() (

(

![]() ) as well as balance

) as well as balance

![]() . The `diagonal' is stronger and

clusters are very balanced.

. The `diagonal' is stronger and

clusters are very balanced.

|

The rest of the results are given in summarized form instead of the more detailed treatment in the example above, since the comparative trends are very clear even at this macro level. Some examples of detailed confusion matrices and pairwise t-tests can be found in our earlier work [SGM00].

For a systematic comparison, ten experiments were performed for each

of the random samples of sizes 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800.

Figure 4.4 shows performance curves in terms of

(relative) mutual information comparing 10 algorithms on 4 data

sets. Each curve shows the difference

![]() in mutual information-based quality

in mutual information-based quality

![]() compared to random partitioning for 5 sample

sizes (at 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800). Error bars indicate

compared to random partitioning for 5 sample

sizes (at 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800). Error bars indicate ![]() 1

standard deviations over 10 experiments. Figure

4.5 shows quality in terms of balance for 4 data

sets in combination with 10 algorithms. Each curve shows the cluster

balance

1

standard deviations over 10 experiments. Figure

4.5 shows quality in terms of balance for 4 data

sets in combination with 10 algorithms. Each curve shows the cluster

balance

![]() for 5 sample sizes (again at 50,

100, 200, 400, and 800). Error bars indicate

for 5 sample sizes (again at 50,

100, 200, 400, and 800). Error bars indicate ![]() 1 standard

deviations over 10 experiments. Figure 4.6

summarizes the results on all four data-sets at the highest sample

size level (

1 standard

deviations over 10 experiments. Figure 4.6

summarizes the results on all four data-sets at the highest sample

size level (![]() ). We also conducted pairwise t-tests at

). We also conducted pairwise t-tests at ![]() to

assure differences in average performance are significant. For

illustration and brevity, we chose to show mean performance with

standard variation bars rather than the t-test results (see our

previous work [SGM00]).

to

assure differences in average performance are significant. For

illustration and brevity, we chose to show mean performance with

standard variation bars rather than the t-test results (see our

previous work [SGM00]).

First, we look at quality in terms of mutual information (figures

4.4, 4.6(a)). With increasing

sample size ![]() , the quality of clusterings tends to

improve. Non-metric (cosine, correlation, Jaccard) graph partitioning

approaches work best on text data (

, the quality of clusterings tends to

improve. Non-metric (cosine, correlation, Jaccard) graph partitioning

approaches work best on text data (

![]() )

followed by non-metric

)

followed by non-metric ![]() -means

approaches. Clearly, a non-metric e.g., dot-product-based similarity

measure is necessary for good quality. Due to the conservative

normalization, depending on the given data-set the maximum obtainable

mutual information (for a perfect classifier!) tends to be around

0.8 to 0.9. A mutual information-based quality around 0.4 and 0.5

(which is approximately 0.3 to 0.4 better than random at

-means

approaches. Clearly, a non-metric e.g., dot-product-based similarity

measure is necessary for good quality. Due to the conservative

normalization, depending on the given data-set the maximum obtainable

mutual information (for a perfect classifier!) tends to be around

0.8 to 0.9. A mutual information-based quality around 0.4 and 0.5

(which is approximately 0.3 to 0.4 better than random at ![]() ) is

an excellent result.4.7Hypergraph partitioning constitutes the third tier. Euclidean

techniques including SOM perform rather poorly. Surprisingly, the SOM

still delivers significantly better than random results despite the

limited expressiveness of the implicitly used Euclidean distances.

The success of SOM is explained with the fact that the Euclidean

distance becomes locally meaningful once the cell-centroids are locked

onto a good cluster.

) is

an excellent result.4.7Hypergraph partitioning constitutes the third tier. Euclidean

techniques including SOM perform rather poorly. Surprisingly, the SOM

still delivers significantly better than random results despite the

limited expressiveness of the implicitly used Euclidean distances.

The success of SOM is explained with the fact that the Euclidean

distance becomes locally meaningful once the cell-centroids are locked

onto a good cluster.

All approaches behaved consistently over the four data-sets with only slightly different scale caused by the different data-sets' complexities. The performance was best on YAHOO and WEBKB followed by N20 and REUT. Interestingly, the gap between GP and KM techniques is wider on YAHOO than on WEBKB. The low performance on REUT is probably due to the high number of classes (82) and their widely varying sizes.

In order to assess which approaches are more suitable for a particular

amount of objects ![]() , we also looked for intersects in the

performance curves of the top algorithms (non-metric GP and KM,

HGP).4.8In our experiments, the curves do not intersect indicating that

ranking of the top performers does not change in the range of data-set

sizes considered.

, we also looked for intersects in the

performance curves of the top algorithms (non-metric GP and KM,

HGP).4.8In our experiments, the curves do not intersect indicating that

ranking of the top performers does not change in the range of data-set

sizes considered.

In terms of balance (figures 4.5,

4.6(b)) the advantages of graph partitioning are

clear. Graph partitioning explicitly tries to achieve balanced

clusters (

![]() ). The second

tier is hypergraph partitioning which is also a balanced technique

(

). The second

tier is hypergraph partitioning which is also a balanced technique

(

![]() ) followed by non-metric

) followed by non-metric

![]() -means approaches (

-means approaches (

![]() ).

Poor balancing is shown by SOM and Euclidean

).

Poor balancing is shown by SOM and Euclidean ![]() -means

(

-means

(

![]() ). Interestingly,

balancedness does not change significantly for the

). Interestingly,

balancedness does not change significantly for the ![]() -means-based

approaches as the number of samples

-means-based

approaches as the number of samples ![]() increases. Graph partitioning

based approaches quickly approach perfect balancing as would be

expected since they are explicitly designed to do so.

increases. Graph partitioning

based approaches quickly approach perfect balancing as would be

expected since they are explicitly designed to do so.

Non-metric graph partitioning is significantly better in terms of mutual information as well as in balance. There is no significant difference in performance amongst the non-metric similarity measures using cosine, correlation, and extended Jaccard. Euclidean distance based approaches do not perform better than random clustering.

|

|

|